|

Courtesy of my employer, the University of Wolverhampton, I received funding to undertake a reccie to Nyae Nyae, homeland of the Ju|’hoansi San in North-eastern Namibia. My aim was to investigate reading/writing literacy among this group of former hunter-gatherers. Personally, I was hoping to find a San writer I could mentor so s/he could write first-hand about the experiences of this, one of the world’s oldest and most marginalized indigenous people.

I was able to coincide my visit with that of Melissa Heckler, founding teacher of the Village Schools Project, which offers culturally-mediated mother–tongue education to Ju|’hoan children in remote areas, so I was keen to learn about this renowned literacy initiative. But first we had to get there. One reaches Nyae Nyae by crossing the African continent, then travelling 670 km north from Windhoek, the capital city of Namibia. We passed troupes of baboon which live in the copper-coloured hills surrounding the city, then entered a seemingly endless savannahscape: dark umbrella-shaped thorn trees protruding above an ocean of bleached grass; families of warthog on calloused knees rooting around on the verges; roan antelope and once, a rare Nyala gazing out from behind a high game fence. The road goes on and on and on and on, but I was with one of the world’s top storytellers so the kilometers flew by. I'd barely registered the turn off to the big meteor crash site near Grootfontein before we were on the 'Great White Way', the gravel road that leads ultimately to the border between Namibia and Botswana. It’s a hot and dusty 5-hour drive through thorn scrub that's tinder-dry after a long drought. Veld fires, set and accidental, are common, and I was relieved that the wide road acted as firebreak to the inferno we encountered on our right-hand side. The not-so-hard shoulder of this road (beware deep, sucking sand turned glassy by the intense heat) was a feeding station for the startlingly coloured lilac-breasted rollers who waited there to gobble up grasshoppers fleeing the flames. I've never seen so many rollers concentrated in one space. They say every bird has 27 colours in its plumage and I can vouch for the fact that the turquoise-blue wings alone are dazzling against the backdrop of charred veld. Finally a transmission tower appeared on the horizon (Remember this tower; it looms large in my new project) and Melissa craned forward. This was her seventeenth trip to the Nyae Nyae Conservancy since she started the first Village school 25 years ago. Some of the Ju|’hoan children she taught are now adults and send their children to Village schools. On this visit Melissa planned to initiate a pre-school program for the new generation of Ju|’hoan children. I had personal reasons for feeling excited. It was 22 years since I‘d visited this area and I hoped to meet up with some of the people who unwittingly inspired my first novel, Salt & Honey. I figured the chances were slim; they were nomadic, the group may have disbanded, people could have died. And I wasn't sure how close to Tsumkwe, the town where I'd be based, they had been. Still, strange things happen in the Kalahari; as Melissa says, you've just got to be there.

5 Comments

I’m not one to accost my icons in public. I once stood next to diminutive Margaret Atwood, she of the towering literary reputation, for fully ten minutes and could not say a word to her. There are, however, two of my heroes that I have made so bold as to approach: Nelson Mandela and Lemn Sissay. I’ve written about my encounter with Madiba, but here’s the one about Lemn Sissay, poet, playwright, broadcaster, recipient of an MBE (‘that’s for Mancunian Black Ethnic,’ he quips) for services to Literature and all-round VIP (Very Inspiring Person). As a Humanities post-graduate of the University of Manchester I rejoiced last year when a poet, Lemn Sissay, pipped a politician, Peter Mandelson, to the post of Chancellor. And he’d done it with a northern accent and all that hair! A few weeks later I heard Sissay interviewed on Radio 4’s Desert Island discs. His take on his extraordinary experience of being fostered and in children’s homes plus his subsequent search for his parents, was fascinating. (See documentaries : ‘Internal Flight’ and http://lemnsissay.com/broadcast-2/video/) A few days later I spotted him in a coffee bar at Euston station. I confess I gawped for a while because I’ve never seen anyone read emails so expressively. He glared, beamed and grimaced at his laptop screen. Even from twenty meters across a commuter crowd, he radiated charisma, reminding me of Madiba. I couldnt resist. Sissay didn’t appear to be displeased by the interruption. He kindly shone his inner light on me for a few minutes and left me in an afterglow. Fast forward to Friday night, and I’m at Wenlock Poetry Festival watching the tour de force that is Lemn Sissay, in performance. Before I attempt a review, let me confess that poetry isn’t my thing; it makes me nervous – too esoteric for a plain prose writer. (Don’t tell my creative writing colleagues, please.) Fortunately Sissay advised the audience not to struggle for understanding, just to enjoy the word pictures and soundscapes. I sat back and did, from the roller coaster of rhyme, assonance and word association that was “Architecture”, to the low static hiss of “Listener”, written to reach out to his lost mother somewhere on the receiving end of the BBC Word Service. (He did eventually find her, in Africa and claims to now have a family as wonderfully dysfunctional as anyone else's.) Poetry was just part of the Sissay performance package. This man has got enough energy to power the Large Hadron Collider. He kept a packed theatre fizzing for more than an hour. He’s a consummate stand-up comedian with topical jokes, hilarious facial expressions, an ability to mime and mimic, and charm by the shed load. He’s generous with his hard-won wisdom, clearly loves conversing with crowds, and shows unshakeable faith in humanity. He was Sissational! Of all the inspiring things he said this is one I needed to hear: “When you think of something, write it down. Write it down like it’s the most important thing in the world. Because if you don’t, it isn’t.” Got it. Thanks, Lemn. This is an emotionally intense week for South Africans, ex-pat and indigenous. On December 5, 2013, the country lost its greatest citizen, Nelson Rohlihlahla Mandela. A journalist from The Guardian newspaper asked if my chance encounter with Madiba nearly twenty years ago, influenced me in in any way? Here's what I wrote in the HE Lives section in response.

With the death of Nelson Mandela – Madiba to South Africans – I've wondered if a chance encounter with him almost 20 years ago wasn't in some way responsible for my academic career and research interest. I bumped into him soon after he'd been freed from prison. I'd emigrated, disillusioned when South Africa's then prime minister , P.W. Botha, vowed never to let "that terrorist" out of jail. The infamous referendum in which the majority of the (white) electorate effectively voted not to change the apartheid status quo, was the last straw. Unlike Madiba, I gave up hope and moved to the UK. It may seem strange, but like most South Africans living under the apartheid regime, I only became aware of Madiba's significance once I'd left the country. Despite growing up in South Africa, I was too young to follow the Rivonia treason trial. By the time I was reading newspapers, all mention of him and the ANC, was banned. The government ensured that he and his comrades were expunged from history books in the segregated school system. Black South African friends remember that the occasional brave teacher whispered his name in their overcrowded classrooms; I was kept ignorant. Once, growing weary of the account of the Afrikaners' ox-wagon expedition into the subcontinent to escape British rule, I dared to ask a teacher if we could study a bit of black history. I was told to "stop being so cheeky". Free Madiba rock concerts came and went but in those pre-internet, pre-budget travel days, we political pariahs had little exposure to international pressure groups such as the anti-apartheid movement. By the time he was finally released from prison I knew Madiba was South Africa's greatest son and sat weeping as he walked out of Pollsmoor looking so diminished. But not internally. Perversely, during his long incarceration, his magnanimity had grown. A year later I was back in my former homeland for a 'new South Africa' holiday. And there, right before me in the busy airport concourse, was Madiba. In those days he wasn't wearing the colourful shirts that became his sartorial trademark; his grey jumper looked disconcertingly prison-issue. But oh, the warmth of the man. I felt no hesitation about approaching him with my two small children. Immediately he bent down from his considerable height, bringing his damaged eyes level with them, asking their names, telling them his father had nicknamed him "trouble-maker", Rohlihlahla. Madiba urged me to consider returning to South Africa as the country needed people like us. I felt unjustly honoured to be included in a group of expats he deemed useful for the rainbow nation he was constructing – but it was too late for us, locked into educational programmes and contracts overseas. I resolved then to try and do something worthwhile for the people of my former land, to try and be bigger than I actually was. Madiba had that effect on people. It took many years before an appropriate route opened up for me. Writing my ethnologically-informed novels (Salt and Honey and Kalahari Passage) about southern Africa's aboriginal people, the San, led me into teaching creative writing in higher education. Which led me into research. Following work with some San students, I've been asked to help with the transformation of their oral folktales into an electronic form. The project is conceived as a way for these thoroughly dispossessed people to represent themselves and their culture to the world. In 2011, I took a San group to meet Archbishop Emeritus, Desmond Tutu. He was enchanted by their storytelling and recognised that his own tribe, the isiXhosa, (Madiba was a clan prince in this tribe) had inherited one of their clicks from San languages. He also proudly acknowledged that he had "Bushman blood" having just taken part in the human genome project. We now know that today's San are the descendants of Africa's first inhabitants, from whom we all come. After the Tutu meeting, one of the San students, Jafta Kapunda, wrote that he had only one more dream to fulfill, to see Madiba. That can't happen now, but I'm sure Madiba would have been delighted to meet these young San, still on their long walk to freedom. Candi Miller teaches creative and professional writing at the University of Wolverhampton and is the tertiary education advisor for the Kalahari People's Network – follow her on Twitter @KalahariPassage Watched 'Greek Myths: Tales of Travelling Heroes' (BBC4. 23/05/12) and am convinced classical historian, Robin Lane Fox is on to something with his hypothesis that landscape inspired ancient stories.

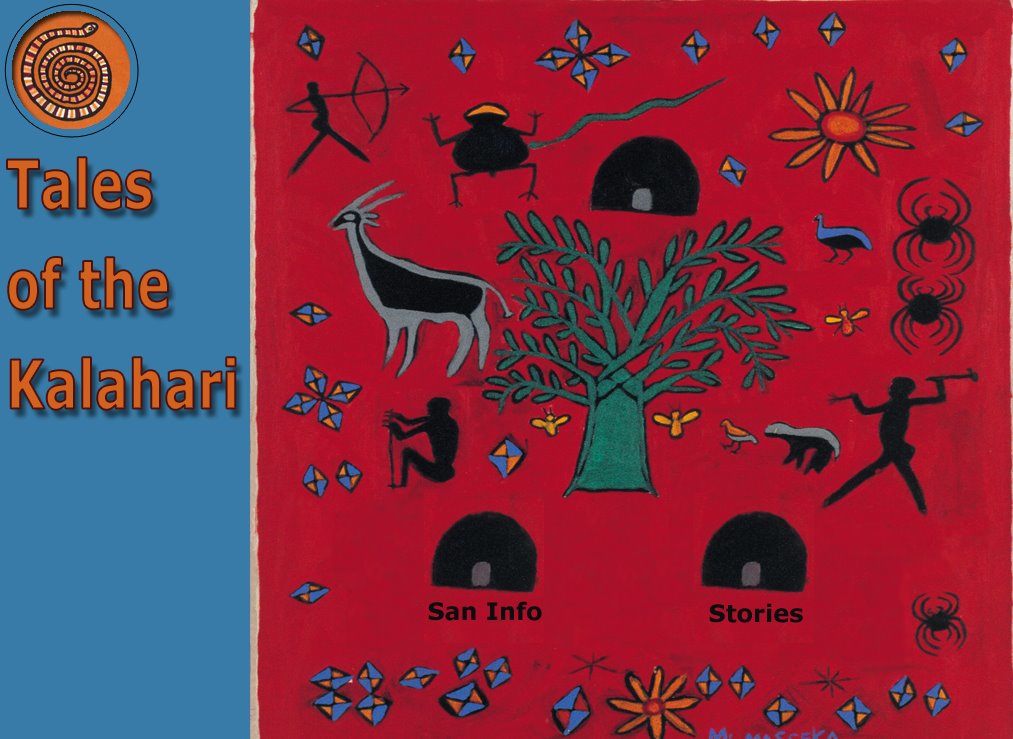

He investigated the origin of Greek myths by visiting sites in modern Turkey with striking topographical features (e.g. Mount Cassios, Bald mountain to the Turks.) It was known, called something else then, to the pre-1200 B.C Hittites. Being the focal point for thunder and lightning in the area, Hittites and their successors believed this summit was home to a fearsome god. Lane Fox suggests that 8th century B.C Greek travellers, the Euboeans, took the tale and made it into their own Zeus. The rest is (classical) history. It occurs to me that one could claim the same type of seed for San stories, which may, for all we know, be far older. Consider the story of Pishiboro, the trickster god and butt of many jokes in some San folktales. There is a cautionary tale about him mistreating a python he encountered. She was lying in a hollow, coiled around her eggs. He defecated on her. (I see you wrinkling your brow and nose, dear reader. Some of the Early Race tales sound shocking to Westerners raised on a diet of sanitised Grimm's fairytales. Remember that those too were never intended for children. For example, did you realise, as a child, that Sleeping Beauty was a tale of rape? (See the writings of Jack Zipes or Sheldon Cashdan should you wish to be awakened from your innocent slumber, princess.) I was clueless, buying into the whole life-giving kiss thing. Yes, he gave her life. Twins. Anyway, I got an inkling that there was something fundamentally incredible in the tale, even for fabulists, some twenty years ago when I told it to a group of San. They had just treated me to an extraordinary folktale about Pythongirl and her jealous sister Jackal. Two minutes into the 'Sleeping Beauty' tale I knew I'd lost my audience. They couldn't willingly suspend disbelief in a tale about a comatose girl wakened by a snog. I had a lot more success with Henny Penny thinking the sky was falling. At this they slapped their thighs laughing at the hen's foolishness, as they do about Pishiboro's. Which reminds me ... back to a scatalogical story which may support an eminent scholar's theories about myth and landscape. Pishiboro torments the python by pooing on her and her brood three times before she's had enough and sinks her fangs into his testicles. They swell to enormous proportions (during this part of a performance the San storyteller will delight in waddling, splay-legged, to demonstrate Pishiboro's discomfort. This gets the crowd thigh slapping.) Pishiboro runs off in pain, across the Kalahari, dragging his testicles, now the size of boulders, through the sand, gouging out the dry riverbeds one can still see in the area today. But Pishiboro finds no relief so he buries his gargantuan gonads in the sand, trying to cool them. Round and round he trundles, boring into the sand until he's made a deep hollow. 'And that is where we get our Kalahari water holes from,' the storyteller will say. Six months since conceiving the idea of publishing ancient San tales in electronic form, I have a prototype digital app (or is it an e-book/anthology? To be discussed…) loaded onto my iPad. Next week I will present the prototype to San trainees gathered at !Khwa ttu, a San cultural and educational centre 70kms from Cape Town.

Here I hope to get an idea of whether this sample of younger San, think transforming their traditional folktales into digital form and disseminating them to readers in the computer-literate world, is a good idea. If they do, we can begin growing this project together. It might seem strange to be talking about the latest in high-end technology and narratology to a people who are newly literate and mostly live beyond the electricity grid, people who have little chance of acquiring, let alone charging a smart phone. Also, of the 11 click language groups in southern Africa, only four, to the best of my knowledge, have an orthography. Given all the above, plus issue of literacy, chances are that the majority of San are not regular computer users. Isn’t it bizarre then, to say nothing of insensitive, to be thinking of making the folktales available on tablet readers and state-of-the-art phones? Since my attendance at a workshop series last year called “Documenting Now, the Story of our Lives” , arranged by the Kalahari People’s Network, I’ve come to believe that the Internet is a place for the San to represent themselves to the world without having to directly confront its challenges. If they can make a bit of money for the coffers of their representative organizations by selling e-books to curious first-worlders, while also gaining some transferable skills for themselves (audio-visual production, professional writing and digital marketing) might this not benefit San communities and individuals? And once the project is funded and working, the folktales could be adapted and used by San children short of resources in their mother tongues, in village schools in the Kalahari. I'm optimistic about mobile learning. Some excellent research has been done to facilitate communication among rural communities. Okay, so we sell the e-book/app to first-worlders and the San kids get ‘em free. But what if there isn’t a large market for the stories? Will it mean the project has failed if what it produces is not commercially viable? No. In this event, at the very least, the project will leave a digital legacy of the extraordinary San folktales. In an era when the San hunter-gathering lifestyle and cultural practices are becoming a distant memory, this might be important. And, if the tales can be told in various San languages, the e-anthology might foster the preservation of certain click-languages. As Wade Davis, who rejoices in the job title of National Geographic Explorer–in-Residence says in his book Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in the Modern World: “A language… is not merely a set of grammatical rules or vocabulary. It is a flash of the human spirit, a vehicle by which the soul of each particular culture comes into the material world. Every language is an old-growth forest of the mind… an ecosystem of spiritual possibilities. (2009: 3) I’m pleased to say that the project concept, at least, has piqued the interest of various organizations working for and with the San — the facilitators at !Khwa ttu, for example, where storytelling has been a theme this past year. The current exhibition at the centre is titled: "Once Upon a Time is NOW: San Stories and Survival. Then there’s film-maker, Richard Wicksteed, whose latest documentary, Bushman Odyssey, charts the journey of a family of displaced Khomani bushmen desperate to return to their traditional land in the Kgalagadi National Park in South Africa. (Thanks to a successful crowd-funding call this film will soon be complete. It will be poignant viewing, I think, given the recent death of the film’s protagonist, Dawid Kruiper, a well-known San rights activist. ) I'm thrilled that Richard Wicksteed has offered training to San interested in audio-visual production. Finally, several San scholars have expressed support for the project too; more about their thoughts on it later. For now, I’d like to establish San opinion. I’m encouraged by feedback from a new San friend, Tomsen Nore, who writes: “The project would ensure the survival of San ancient stories in the wake of rapid technological advancement and development. Post modern man walking around with ancient San folktale in a handset… so amazing.” Made it! Delivered the draft storyboard for the San e-tale app by deadline.

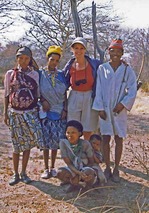

This involved a far-too brief recce around the subject of app design, so if anyone has suggestions about well-designed enhanced e-books for further study, please let me know. Right now my gold standard is an iPad app made by Touch Press, T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland. Take a look. It’s ravishing. Max Whitby, Managing Director of Touchpress, gave me a rough cost indication for what he calls ‘a moderately sophisticated interactive book of the kind we publish’… The estimate was‘ £75k to £150k. ‘ Eeek! Not having that kind of budget (nor any at all at this stage) I had to do what I could. Using App Scribbles and Publishing layout I tracker-padded a sketch of an eland and a group of San elders squatting around a fire. As you can see from the above, no professional illustrators need fear for their jobs Drawing a traditional San village (the portal page for the proposed app) defeated me. To my rescue came Jobe Gabotowe, currently in residence at a San cultural centre in South Africa where they have a replica village. Quick as a flash he snapped a shot and emailed it to me. Jobe is one of a cohort of omnicompetent young San I had the good fortune to meet at a workshop in South Africa in August last year. A Khwe man from Botswana, Jobe is a qualified tour guide currently undertaking curatorship training at Iziko Museum in South Africa. He is one of the Young San Writers fast developing a powerful voice. Read his account of his growing awareness of injustice suffered by the San, past and present, here: I hope to be able to consult these tech-savvy future custodians of San culture, about my project. Perhaps we could convene for a reunion at !Khwa ttu? In the meantime, let’s hope my storyboard does it for the fellas from the uni’s IT Futures team who are submitting costings for designing a prototype app based on this storyboard. Last week I spent the day at MediaCity, the BBC's brand new HQ in the north, courtesy of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) New Generation Thinkers scheme. MediaCity is a metro-sexy-looking place, with tall buildings condomed in sleek glass or copper or stainless steel. It overlooks the reclaimed Salford Quays. It was grey day. Even Robbie what’s-his-name from Strictly Can’t Dance couldn’t brighten it as he jogged past, all über-tanned torso and over-blond locks. It’s my impression that it’s always grey in Manchester. I did a degree there and can't remember the sun shining once. Fortunately the folk up north are warm and friendly and allowed us to ogle as we stepped into a penthouse-style space called the Imagine room. I tried to imagine what it has cost the license payer but lost count while drooling over the Armani-looking sofas. Shifting my gawp from the million-pound views, I found myself surrounded by bright young things, from the BBC staffers to my ‘rival’ academics. I settled my specs on my nose and reflected on the consequences of having had other careers first. The New Generation Thinkers scheme is a clever one, providing as it does an ever-widening pool of pundits for the Beeb to call upon when they need panelists or interviewees. And for academics, it ticks the Impact box in the Research Excellence Framework (REF) form, so it's win-win. (If you don't know what I'm talking about re REF, keep it that way. The research imperative in UK universities is onerous these days, especially for someone like me who never meant to be an academic.) But there I was and soon enjoying myself listening to and discussing the key elements of good Arts and Culture programmes. It struck me that these dovetailed with the elements of good feature writing which I teach to my Journalism students, i.e. start with a hook, use vivid detail to create word pictures, match your tone to your subject matter, present your argument with clarity and consistency and don't shy away from the personal. I thought it was much harder to embrace the facilitate-stimulate-detonate qualities of a good presenter of panel discussion on public radio. Academic etiquette dictates that one allows one's debating adversary as much time as they’d like to pontificate, obfuscate or annihilate themselves in an argument. Clocks do not tick loudly in ivory towers so seldom does one academic have to baldly point out (especially within the adversary’s hearing) that they are talking tosh. This, however, can make for interesting radio, we gathered from various clips played to us. But the dissing was missing as we floundered around the banal topic of ‘Is life comedy or tragedy?’ in a dispiriting tag team debate. In desperation, while briefly occupying the Presenter’s chair, I labelled the argument of an admirably spiritual biographer from Hull as ‘base’. It wasn't; very high-minded actually, but he was supposed to be arguing for comedy.) My declaration evoked an un-zen-like riposte. Later I hissed ‘bastard to a sweet-faced fellow from somewhere up north who trapped me into showing the comic underbelly of my argument while I sat uncomfortably in the Tragedy chair. A shame you couldn't see my 'fair cop' grin on radio. I hope the chaps won’t hold it against me. It was all in the spirit of getting them to drop their academic drawers in public. I think I did better with my mini-thesis pitch though I forgot to mention the dangerous and exciting bits, namely, that my field trip had placed me in the path of an irate bull elephant and a veld-fire the size of a subcontinent — which I had to flee in a fuel-laden Land Rover wheel-spinning in sand turned molten by the surrounding inferno. On second thoughts, I probably didn’t need that bit. I probably said enough dangerously exciting things at the BBC for one day. The BBC/AHRC New Generation Thinkers 2012 finalists will be announced at the end of April. A long time ago, the band of San people pictured here, allowed me a glimpse into their way of life.

An arduous journey had taken me far beyond the tarred road's end into the Namibian part of the Kalahari desert. There I found a small band of click-language speakers, Ju|'hoansi, specifically, who were trying to live off veld food: roots, berries, leaves and the odd game bird. They hadn’t seen ‘big meat animals' in decades; game fences had long ago put paid to the migration of the vast herds of antelope that used to traverse the Ju|’hoan’s traditional hunting grounds. I was there not as an anthropologist, but simply as a rookie novelist. I wanted to tell a story about a San girl but with some ethnological accuracy. I’d read everything I could find in those pre-internet, pre-university library access days. Anyway, as a writer I needed to know exactly what colour the Kalahari sand my character would squat in, was. And what the skin of the baobab fruit felt like. (Short pile velvet.) Slowly, shyly, the band and I became acquainted and eventually I was able to go out gathering and tracking with them and was invited to sit around their campfire listening to a traditional story. It was a seminal moment and when I left the people said: ‘Don't throw us away’. More than ten years later, I still hadn’t managed to find a publisher for the novel the trip had sparked. But in 2006 Salt & Honey was picked up and published by a then fledgling imprint called Legend Press. Naïvely I imagined that it would sell millions or the film rights would be optioned by Angelina Jolie, mad for things Namibian having just given birth there to her first child. I saw myself gifting the San who’d been so generous with me. It was not to be. In the end, thanks mostly to the sale of foreign rights, I was lucky to get back the money I’d borrowed from family savings in order to finance my research trip. Proud as I am of the sequel, Kalahari Passage (Tindal Street press, 2011) I’m not convinced it’s going to make anyone’s fortune either. Which is fine. I didn’t write about Koba to make money or a name for myself, but because I felt a wider world than that of San scholars should know about the injustices suffered by these gentle indigenous groups. But this leaves me with a debt still unpaid to the people of the Kalahari. It’s for this reason that I’d now like to explore the feasibility of using digital technology to allow the San to capture and collate story-telling material, use it to create an app, market it and profit from any sales. My project is tentatively titled ‘From Kalahari campfire to cyberspace: turning an oral folktale into an enhanced e-book.’ More utilitarian than catchy, so feel free to make suggestions. I am indebted to colleagues at the University of Wolverhampton for their help with this, especially those in the Project Support Office and in the Centre for Transnational and Transcultural Research. My thanks in advance to my patient and knowledgeable external advisors, Dr Megan Biesele and Marlene Winberg. I fear they are going to shudder everytime they see an email from me land in their Inboxes. I have much to learn from them and from San I’m eager to include just as soon as I secure funding for this project. Wish me luck as try to get this seed to sprout. And if you have any information which might help the project along, please, please share it. |

AuthorAfrican novelist and out-to-grass, academic. Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed