|

An account of a nail-biting trip to attend an amazing San cultural event in Botswana in 2012.

'There's a spare seat in a car going to the Kuru Dance Festival. Want it?' asked a fellow San supporter. Did I want it? For as long as I've been researching the ways of these indigenous hunter-gatherers of southern Africa (about two decades) I'd dreamed of seeing them perform their age-old trance dance ritual. Grainy film footage and, in later years, high-fidelity recordings, did nothing to convey the alleged spiritual power of San shamans. Also, I’d heard reports that this ancient healing custom was dying out as the dispossessed San are forced to relocate to urban areas, their traditional music and dance swamped by waves of relentless rap and grinding hip-hop. Here was a chance to see traditional trance dancing under a full moon, surrounded by unspoilt African bush. I grabbed the last seat in that car as fast as you can say ‘lend me a sleeping bag’. Day 2 Cape Town sparkles at the green tip of South Africa. It is oceans, vineyards and verdant glens away from Ghanzi, a Kalahari desert town in Western Botswana where the Kuru dance festival would be held. We set off on our 1 000 mile-journey before dawn leaving the Mother City to slumber under Table mountain’s down-duvet. Four hours later we were at the foothills of the Cedarberg range marvelling at the rugged reflection of the peaks in the Clanwilliam dam. Archaeologist estimate that the mountains are home to more than 2000 rock art sites. Under overhangs and high up on sandstone cliffs one can see the ancient therianthrophic figures that characterise San rock art. (I visited some of these sites the year before in the company of some San who, like me, had heard about the murals attributed to their ancestors, but never actually seen them. Our guide, John Parkington, Emeritus professor of Archaeology at the University of Cape Town, explained how the painters’ red pigment might have been made. One of the San shyly volunteered that in his homeland they still get a red pigment from the bark of a certain tree. 'But not for painting spirit-things,' Tsamgxao Cwi mourned.) At this time of year, very early spring, the Cedarberg resembles Switzerland in summer. The valleys are green and blanketed with wild flowers, flashy Namaqualand daisies that transform this normally arid area into a photo opportunity. I wasn't given the chance to stop and snap; we still had a subcontinent to cross. Technicolor and tarred road gave way to the lunar landscape behind the range. Beige and brown now. Boulders, dust, no visible water, the dirt road rattled us over precipices and passed caves where I imagine the first people lived, millennia ago. From this vantage point they could keep an eye on the herds of antelope that must have roamed the plain before us. Now it was empty, not even a rusting windmill to puncture the flat-line horizon, nothing but us, beetling northwards, our dust trail the only evidence of recent human passage. A news report on the car radio about San archaeological finds elsewhere in South Africa. Arrowheads made from bone and ostrich eggshell jewellery have been dated to 44 000 years ago. Ha, take that, ye governments (past and present, black and white) who claim that the land your pastoralist forefathers settled in this part of the world was devoid of human habitation at the time. Don’tcha just love it when synchronicity sends a blessing? Eventually we reach Calvinia, one of several remote, single petrol pump-towns with an imposing Dutch Reformed church and little else. Mind you, the homemade milk tart was good. I ate it in a restaurant with an enormous faux rock arrangement in the middle. Why, I wonder? My travelling companions are an interesting bunch: Jobe and Magdalena, from two of the 20-odd San language groups resident in Botswana, Namibia and to a lesser extent, Angola and South Africa. As trainee curators, this pair are festival-bound to identify a dance troupe to invite to !Khwa ttu, the San cultural and educational centre outside Cape Town where they are currently based. I take the opportunity of the long car journey to discuss with them the challenges of turning traditional San folk tales into an e-book. They are enthusiastic. Jobe, in his deceptively laid-back drawl, labels it as ‘Chapter One’ of the digital app idea I’d originally had. (I haven’t abandoned that idea, just become more realistic about how enormous the task is. Having a ‘practice run’ via the e-book will be instructive for all concerned.) The driver and owner of the car is Felix Holm, a veteran of trips into inaccessible areas. He deals in traditional African crafts. I am interested to learn about issues surrounding the commercialisation of this business. I’d imagined that sensitive intermediaries like Felix would be a godsend for San looking to sell their beadwork outside of the Kalahari. So they are, helping poverty-stricken families to earn some cash. But the trade has led to the San being introduced to labour-saving devices such as automatic drills. While these increase output and save the teeth of the bead makers, says Felix, they also subtly alter the original product and may result in industrial waste, albeit micro-scaled. Instead of bead making leaving a detritus of organic matter (plant twine and eggshell chips for example) there is now non-biodegradable debris littering the bush. Felix guns his well-worn Fiat Multipla towards the Botswana border, entertaining us with tales about his Afrikaner ancestors. One anecdote has all the makings of a Wilbur Smith bestseller – more than a century ago, a branch of the family, Boers fed up with the living under British rule at the Cape Colony, set off into the interior along with their servants, cattle and children. They clashed with Black pastoralists and in a raid the entire family was massacred, save for newly born twins. The boys were saved because their black nursemaid hid from the marauders, apparently suckling the babies to keep them quiet. (I bet the Vroue Federasi has something to say about that!) The maid returned to her tribal village with them, where, several years later, a party of trek Boers came across the blond-haired boys and reclaimed them. They went on to feature in Anglo-Boer history. Late at night we reach our overnight stop, Bokspits, on the edge of the Kalahari desert. The ground is frost-hard as I pitch my tent. Day 3 I wake refreshed, keen to see the ranks of red sand dunes that characterise the southern Kalahari. No time to stop and sand surf, the moon is waxing – night after next it will be full-fat and the trance dances must begin. We have hundreds and hundreds of miles to drive yet. And drive we do, reaching the shimmering asphalt of the Transkalahari highway at midday. Here is cattle country grazed bare. Hungry herds have broken through fences to reach the stalks on the verges of the highway. It makes speed unwise and our slow progress agitates Felix who warns that the highway is a nocturnal no-no. “Then this road’s like a donkey dormitory. Something about their coats absorbs light so they’re impossible to spot till it's too late.' He drives as fast as he dares, but almost immediately warning lights flash on the Fiat's dashboard. Felix stops, gets out and peers under the hood. No sign of overheating. We all hold our breath as he waits before turning the key. The car starts immediately. Whew! Passing vehicles are few and far between. 10 miles further on and the Fiat's dashboard starts flashing like a Xmas tree. The engine falters. Falter is followed by stutter and stutter by stall. We stop and Felix pores over the manual. “I think we better find a place for the night.” There is one 20 miles away; stopping and starting, cajoling the car and cursing it, we eventually make it, cheering when we see thatch-roofed rondawels. They have space, a troglodyte tent, khaki canvas partially encased in faux rock. Faux rock seems to be the rage here. I sleep in a proper bed, but not well; too busy mulling over the cruel possibility of being stranded just two hours from my dream destination should the Multipla not start next morning. It doesn’t. I whisper to Felix that I’d overhead a couple talking about the Kuru Dance festival in the dining room the night before. I’d noticed them, as they were chomping on the biggest steaks I’d ever seen. Now we approach them and Thandi and Isaac agree to transport Jobe, Magdalena and I, as well as the trailer of camping gear. They are lively company and I am pleased to offer them lunch when we arrive at our accommodation, the very pleasant Thakadu Bush camp. (No faux rock.) The extensive game meat menu pleases: warthog, eland, springbok, kudu. Botswana is carnivore’s heaven. It’s salad and fresh veg that are luxuries here. Our rescuers leave and we face up to our ongoing transport problem. Granted we are just 35 miles from the festival site, but we may as well be back in Cape Town. First there’s the long bush hike back to the highway. Once there, no guarantee of a lift; Kuru is beyond Ghanzi, the nearest town. I hear there is a taxi driver in Ghanzi – he isn’t taking calls. In desperation I grovel over to a group hosting a children’s birthday party. They seem to be watching a real warthog kneeling at the waterhole to drink? And soon eland are startled from a thorn thicket by strains of “Happy Birthday to you.” I get into conversation with two aunties trying to keep flies off Little Mermaid’s iced tail. They turned out to be the famous ‘white-San’ sisters, Polly and Ada Harbattle. Here’s another Wilbur Smith saga: their father, a white rancher from England, took a San woman as wife. Instead of keeping his ‘half-caste ‘ family hidden in a hut, as polite ex-pat society would have preferred, he proudly acknowledged them and sent them off to England to be schooled. The Hardbattles are soft; warm and humorous about their straitened circumstances. They too need a lift to the festival as their ‘old bangers’ aren’t up to the off-road trip, they explain. I retire to my tent, defeated. I spot a Nissan negotiating the challenging game lodge road. Success. It parks at the next campsite. Two smart young Botswanans I will come to know as Kgalaletso (Glorious) and Onalenna (He is with me) hop out. They have driven 500km to have a girls’ weekend at the dance festival. Yes, we can tag along. On arrival at the game farm, now called the Kuru Conservancy, we learn that the festival site is another seven miles into the bush. The sentries at the gate shake their heads at the Nissan and its intrepid driver. We must hitch a ride (story of my life) in a four-wheel drive vehicle; one will be along, eventually… The moon rises higher and higher, beaming down on trance dancers somewhere deep in darkness I can’t penetrate. I try to block my ears against the sound of far too distant drumming. Cars pitch up, a surprising number considering how far on the road to nowhere we are. None have space for extra passengers, not even two let alone the five of us! An hour inches by, it’s getting winter-desert-at-midnight cold. I kick stones to keep the circulation going in my numbed feet. Finally a 4WD vehicle with just a driver pulls up. He’ll take us. Another half hour and a lot of gear-grinding later, we are there! But what’s this concrete structure? I’d anticipated a campfire, not this ugly, open-air auditorium. Once inside I appreciate the protection it offers from the chill wind. And the raked seating; there are rows and rows of spectators. Oh heck, is this going to be San culture canned for the masses? A troupe of elderly-looking people files into the arena wearing skins and dance rattles. Their loincloths and pubic aprons are well crafted and well worn. They have beautiful beaded headbands and ornaments. Ahh, this is no tourist getup, it’s the real thing and I’m seeing it. How-lucky-am-?! The women sit in a semi-circle and begin clapping a complicated rhythm. One voice lights up, bright as a flare shooting into the ancestral sky. Others join in. I’m having a goosebump moment. Men shuffle around and around the singers and soon kick up a veil of dust that shines like fiery gauze. Suddenly a dancer buckles at the knees. He is caught by minders who lay him on the ground. His body stiffens, his legs shake, the hairs on the back of my neck rise as his back arches in a convulsion. This must be the n|omkxao, the owner of medicine. Oh-oh-oh! I hold my breath until woozily he stands up again. But now he digs into his armpits for the n|om, the healing power he has summoned from his spirit guide. He lays hands on people. They seem to swoon and unbidden into my brain comes ‘Lynx-effect’. I feel like a child caught being disrespectful in church. Better close my eyes and open my heart. I hear/feel clapbeat, heartbeat, clapbeat, heartbeat; chanting like a muscular mantra. Warmth around my shoulders now despite the sneaky wind. I feel the knots in my neck loosen. ‘It is over; it is finished,’ scolds a deeply disappointed voice via the P.A. system. I jerk out of my meditation. ‘People have disrespected the tradition!’ But it isn’t my anti-perspirant thoughts that have spoiled things. Flash photography, expressly forbidden at the night event, is ruining the shaman’s concentration. And so this extraordinary experience is cut short. As I stumble, disconcerted, out of the stadium, I remember the author, John Fowles, writing about photographing the glory of a butterfly. So busy was he capturing it on film, he never really saw it, he wrote. I have permission to do some photography at the festival tomorrow. I vowed to remember just to look, too. Day 4 Next day we again get a 'Glorious' lift to Kuru and this time quickly secure a ride over the thumps and bumps. Today the conservancy teems with more people than game. The car park is so full even the ‘attendant’, a fully-grown ostrich, is having trouble ‘patrolling’ between the vehicles. A surprising number of non-San dance troupes are listed on the programme. They’ve travelled from far and wide, courtesy of sponsorship from the biggest gem diamond-mining group in the world, Debswana, a partnership between De Beers and the Botswana government. The company’s ubiquitous banners boast about Debswana’s contribution to local communities. I wonder how literate San view these. My understanding is that while some Tswana societies have had schools and roads built by Debswana, San communities who live less than a dozen miles from a mine (e.g. those at Kedia who live near to the Orapa mine) have been completely ignored. Credit to the savvy young San who organised this Kuru Dance festival, I think, for finally getting Debswana to put some money on the table for the San. The other PR coup for the 2012 festival organisers lay in persuading performers from other ethnic groups to participate in what is seen as a San cultural celebration. Despite evidence that vast tracts of what is now Botswana belonged to San hunter-gatherers, the Naro or Nharo, the largest San language group in Bots, are now a marginalised people, many eking out an existence as labourers on settler farms and in some cases living as serfs among their Herero landlords. The fact that the stadium was packed with Tswanans showed that many are curious about San culture; they also have respect for San healers, consulting them when their own healers have failed. The Bots. Government, however, seems determined to colonise the San, both in terms of their land and language. I am grateful for the shade of the stadium canopy as I watch troupe after troupe of dancers stamp, clap, drum, and leap, strutting their stuff in an array of traditional dress, from shimmying raffia skirts to the stately Victorian-style dresses of the Herero women. While I love the verve and energy of the young people who mostly make up the non-San troupes, it is the elderly San troupes that really move me. Today the singing seems particularly pure, and the narratives contained in the dance are both instructive and dramatic. Chuckle-chuckle at sly San humour when one shaman pulls out a stethoscope during the healing ceremony. I find the audience as fascinating as the dancing – a kaleidoscope of skin colours and head gear; striking juxtapositions: white man, paparazzi lens thrusting through young San bucks in skin breech clouts and duiker horn- head dresses. A slight San next to a massive Herero. Text message from Felix, still stuck 250 miles away. The car needs a specialist mechanic and spare part. A week or more. Poor guy. And eeek! I have a lawyer's meeting about San intellectual property rights that I'm anxious about back in Cape Town. I can't afford to cancel again. I need to get to an airport, but where, how? Thandi, who gave me my first lift, spots me and calls me over to meet her Swedish friend, Elisabet. We chat; I tell her I have only been to Sweden once, to a tiny place, a mere railway siding inside the Arctic Circle called Porjus. ‘I used to live in Porjus,’ Elisabet laughs. The talk turns to dance, then to tango. We are both students and have mutual dance partners. This is getting too weird. I am stranded in the Botswana bush without my stilettos and need to hustle. I work the crowd and finally land a linguist travelling to Namibia the next day. He’ll drop me at Windhoek airport. Now there is one last lift to find, my final shuttle between Kuru and the Transkalahari highway, between this world of wondrous coincidences and the mechanised maelstrom out there. But the gifts this experience has bestowed aren’t over yet. A local white rancher offers me a ride. What follows is as accurate a record of our conversation as my memory will muster. I include it especially for some of my readers who have baulked at the dialogue of characters like Etienne and André Marais, Boer bosses in Salt & Honey and Kalahari Passage. Me: Do you employ San on your cattle ranch? Him: Ja, some, but they’re no good. Me: Er, in what way? Him: Lazy. These are desert men, hey. They don’t expend any unnecessary energy. Useless when it comes to making fence posts. Takes them weeks. Ja-no, for fence posts you need a Zimbabwean. A Zimbo can chop wood all day; chop till he drops. But he can’t set a fence straight; posts all over the show. Ask him what the hell happened, he’ll tell you the cattle leaned on them. Now your Bushman, er San, he can run a fence straight as an arrow, across any kind of terrain. And it makes sense. These okes are used to walking everywhere in this bush without Sat Nav, so they don’t take the long way round.” ‘Ja-no’, as my Afrikaans characters say, my trip to Kuru was an inspiration, in all sorts of ways.

0 Comments

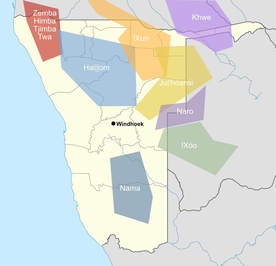

I’m going to tell you a true story… In 2012, a group of trackers from Nhoma village set out to accompany a tourist on a bushwalk. Despite the fact that money-earning opportunities for the Ju|’hoansi are few and far between, they were, reportedly, reluctant. A veld fire had been raging all night and Arno Oosthuizen, the owner of the hunting camp, wanted them to take a client to an area they felt would place them in danger should the wind change direction. The trackers lost the argument and set off, wearing only traditional loin cloths, as requested. The wind did change direction and it picked up speed. Mightily. The party found themselves unable to outrun it, trapped on all sides. Frantically they cleared bush to make a firebreak, but they could see it wouldn’t save them. So they dug a hole in sand, one of the survivors told me, and placing the tourist in it, they all lay on top of her. The fire raced over them, burning 3 of the San men very badly, so badly that one tracker’s foot fell off afterwards when he tried to stand. The tourist, an Australian woman called Jane Bean, accompanied by one of the less burned men (the only one who was wearing Western dress) hiked back through the bush to get help. Ms Bean was transferred to a hospital in the nearest large town, but the Bushmen (a name they use for themselves now) were taken to a local clinic. After a few days Bean motivated for their transfer to a burns unit in the capital city. It was too late for two of her guides. Tragically, one had died from dehydration at the clinic. The other two, a pair of brothers whom I met, one of whom related the events to me, survived, after extended stays in hospital. I haven’t told you the names of these men because they are both discomforted by the publicity this story attracted. San (Bushmen) culture is predicated upon egalitarianism. Being in the limelight is anathema to them. Also, they are clearly still traumatized. During our meeting, I asked them for permission to dramatise their ordeal for a pilot episode of the khuitzima, the Ju|’hoan radio drama, and they agreed. They had no wish to participate themselves. Unfortunately the radio drama pilot was never made as funding efforts failed. If you'd like to learn more about the event described above, here are some links. San men sacrifice themselves for Australian tourist - YouTube. As promised to the proposed project stakeholders, the NBC (Namibian Broadcasting Corporation) and the head of the Ju|’hoan traditional authority, Tsamkxao ǂOma, 'chief' Bobo,, we, i.e. the !Ah radio station manager, the late Teresia Mieze, interpereter and San council member, Kallie and I, have travelled north, south, east and west of the transmission tower, mostly off-road to talk to Ju|'hoan people about the idea. It’s been a shuddering, juddering, sometimes swampy three weeks (we bogged down axle-deep in mud trying to circumvent a pan of water that had obliterated the road) but it’s been encouraging. After hearing of the idea to make an on-going radio show with the Namibian Broadcasting Corporation using local talent, villagers clapped and said “we wish you could start today!” In one settlement the children chanted: ‘We are ready for the project, we are ready, we are ready!” Quick aside: in this same village, Ben se Kamp, I noticed a boy behind the squatting adults. He was grinning at me and waggling his fingers on his head. Then he flapped his folded arms at his side like wings. Of course! He’d been in the class I’d done storytelling with the previous year. He must have remembered the story they made up about a guinea fowl mother who saves her children from a hyena. I certainly did. It was a great story, a brilliant example of the collaborative learning the San are so good at. Afterwards the kids did a triumphant guineafowl dance around the tented classroom, waggling their fingers like guinea fowl coxcombs. The funding stream I’m targeting is the UNESCO International Fund for Cultural Development. However, applications only open in December 2017 and approved projects can only begin in March 2019. Sigh. We have now visited 14 of the current 37 Ju|’hoan villages and approval of the proposed idea has been universal. I’ve learned that functioning radios are in short supply and that listeners want more Ju|’hoan native speakers as announcers. I’ve also heard stories that I think will make excellent material for the drama, and I’ve met individuals who are obviously naturally talented performers. Most importantly, it’s become clear that everyone wants a chance to audition if/when we secure funding for the khuitzima. Gasp. That could be hundreds of people coming in from the outlying villages alone. And they’ll have to be housed and fed. The logistics are daunting. I discuss the problem with Melissa Heckler and Prof Bob Hitchcock. He’s co-director of the Kalahari People’s Fund. (Yes, the one I ask buyers of my novels to donate to in lieu of a purchase price.) They have a great idea – a storytelling festival, all interested parties invited, and the NBC recording performances as a way to build up a database of actors and material for the drama. Bruce Parcher, in charge of San Culture and Education for TUCSIN (The University Centre for Study in Namibia) says they can help too. Whew! “Let’s call a halt on visiting villages,“ I tell Teresia and Kallie. “You’ve got a radio station. Let’s use it to broadcast news of the khuitzima. So we did, and in the process discovered that Kallie is a pretty good announcer.  Drove 800 km north out of Windhoek, no problem. Passed ostrich, baboon, warthog, lilac-breasted rollers (no fire this time – see link), bee eaters, pale chanting goshawk and some exotic road signs. Then, disaster… we stopped overnight and I locked the keys for the hire car in the boot. I was informed a spare would take one week to reach me. Impossible. Also, the courier cost was prohibitive. “Break the window, remove the seat and pay for repairs,” advised Hertz. “Ag,no, what,” said Stephan, owner of the excellent Seiderap guesthouse in Grootfontein. “Lemme have a go.” So, between cooking delicious courses and topping up guest wine glasses, Stephan popped out with a bent wire and popped the lock. I can definitely recommend that stopover! The next afternoon we — I was with my trusty Kalahari travelling companion, Melissa Heckler, founding teacher of the Village Schools in Nyae Nyae. She was returning to expand the pre-school education project she’s started — drove into Tsumkwe, home to !Ah radio. With a floating population of approximately 1500, it’s the largest town in the arid Nyae Nye Conservancy. Amazingly, Tsumkwe looked like it had been plopped down into the Lake District. Green shrubs, green grass, large bodies of blue water, where before there’d been parched earth and bushes grey with dust. Coot and teal hooted and quacked as we drove over a section of road that was now a bridge. I spotted a turtle clambering up the trunk of a submerged tree. Where the heck had it been during the drought years? Next morning I called in at the NBC, was welcomed warmly, and immediately we were off to find the head of the traditional authority in the region, a man known affectionately as "Chief" Bobo. The chief was not in his usual abode. “He’s gone Bushmen,” his son, #Oma Leon quipped. He explained his father was out harvesting Kamaku, Devil’s Claw, a root sold to big pharma for use in countless health products. Kamaku is hell to harvest. The tell tale surface tendril is difficult to spot, and handling the prickly bulb lacerates the fingers. As natural ecologists, some say the world’s oldest, the Ju|’hoansi ensure the mother plant is left intact to grow next year’s crop. Digging Devil’s Claw is seasonal work and poorly paid, but it’s one of the few sources of income for many residents of the area. After a lot of off-road driving, we came upon four OAPS who were clearly in their happy place, a peaceful bush camp under lacy trees. The old wives sat under on the ground, legs outstretched, chatting and laughing as they sliced the murderous root. The chief’s brother-in-law whittled away at a new walking stick, fashioning a head of white much like his own. Tsamkxao ǂOma, Chief Bobo, received us graciously. To paraphrase the translation made for me: "He is thanking us for driving out to find him." Chief Bobo listened keenly as my interpreter outlined the project, then beaming through over-large blue plastic spectacles, he launched into a statesmanlike speech: “This khuitzima (lit. radio role play) is a very good opportunity for the Ju|’hoan to present their culture and talent to other people in Namibia, and even beyond Namibia. People must realize this work is long-term; it’s a project not just for them but for their children too....” Translation provided by Kallie N!ani Kagece of the Tribal Authority office 'Chief' Bobo asked me to visit as many Ju|’hoan villages as possible to get the approval and input of the people. Consensus is the San way. I agreed, little knowing how many there were and how arduous travel conditions would be over the next few weeks, in the soggy Kalahari desert. “We’ll translate it into other languages and broadcast across Namibia. And ... make a TV show too. Everyone must see what the San can do.”  San language group distribution, Namibia & surrounds. San language group distribution, Namibia & surrounds. Do you remember that idea I had for an educational radio drama to be made for Ju|’hoan listeners in conjunction with the Namibian Broadcasting Corporation (NBC)? Well, my employer, the University of Wolverhampton, thought the idea good enough to invest in, so they sponsored a fact-finding mission to establish stakeholder interest in the proposal. I was also to secure the necessary permissions prior to applying for external funding for the project. I began my trip in Windhoek, capital city of Namibia, where I was invited by my future bid partner, Ms Menesia Muinjo, to her management meeting to present the idea. Menesia is the charming Head of News and Programming. Effortlessly she combines the roles of boss, friend and mother, motivating a team to produce daily broadcasts across 10 radio stations and 3 television channels, sometimes for up to 18 hours a day, despite very limited resources – i.e. untrained staff, outdated equipment and a budget most BBC execs. wouldn’t get out of bed for. The NBC are fired up about making a radio drama using the talents of local Ju|’hoan speakers and have a far-reaching vision for it. “We’ll translate it into other languages and broadcast across Namibia. And our DG [NBC Director General, Mr Similo] wants us to make a TV show too. Everyone must see what the San can do,” Menesia bubbled. We began gathering approval for the idea from stakeholders and their representatives. Menesia had a hotline to the musically named, Hon. Royal /Ui/o/oo, Deputy Minister of Marginalized Communities in Namibia. (Suck your teeth for the first syllable, then make a champagne cork-popping sound twice, for the next two. Cha-cha for the tongue.) He enthused at length and segued into requesting a drama for every San group. (You may recall that the Ju|’hoan are one of several groups of click-language speakers still found in Namibia.) Meanwhile I visited Kileni Fernandu, secretary of the newly formed San Council of Namibia. I felt apprehensive; she has a reputation as fierce guardian of San rights. No doubt she is, but also extremely courteous, (I’ve never felt as closely listened to as I did by this young woman) warm and helpful. Can't wait to share koeksusters with her again. Next, a meeting with the Director of Adult Literacy in Namibia, Mr Beans (yes, really!) Ngatjiseko and his team, about dovetailing the drama with the Adult Literacy curriculum and literacy promoters in the province of Otjozondjupa in some way, when the time comes. Fine in theory, but they too operate under severe budget constraints in a country where government spending is being curbed. Finally, it was time to take my idea to the people of Nyae Nyae. Menesia put the NBC’s four-wheel truck and off-road driver, the station manager of !Ah radio herself, at my disposal in Nyae Nyae. All I had to do now was get there.

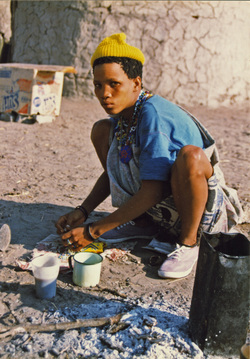

I began to ponder the creation of a self-perpetuating stream of content for !Ah radio. It could address local issues but in an edutainment way. How? Via a radio drama, what used to be called a Radio Soap, back in the day. (Growing up in South Africa I was an avid listener of Lux radio theatre.) It seemed to me, that encounters with elephant or lion aside, the day-to-dayness of living in the rural community which is Tsumkwe and surrounds might be something like life in the fictional farming town of a long-running radio drama on the BBC called ‘The Archers’. No-one in The Archers has to go to bed hungry, as far as I know, nor walk 25km to get to a clinic, but I was thinking about the characters – people of the land, old and young, neighbours and relatives and the things that befall them. Sometimes The Archers does melodrama. Well! Who could forget Helen's trial for the stabbing of her abusive husband. I recalled a real-life tragedy in Tsumkwe, when a man stabbed his beautiful wife to death. Unlike The Archers the weapon to hand was an antelope horn rather than a kitchen knife. An African Archers for the people of the Nyae Nyae, is what I imagined. The staff at !Ah were very keen on the idea of using local talent to create a radio drama and confirmed what I already knew – that the Ju|’hoan are great oral performers. If scripts could be produced, actors would be found, they assured me. But I’d have to get the station owner, the Namibian Broadcasting Corporation (NBC) on board. Back in Windhoek, I secured a meeting with Glynis Beukes-Kapa, executive producer of educational content at NBC. She immediately arranged for me to pitch the drama idea to her boss, Ms Menesia Muinjo, Chief of News and Programming. Ms Muinjo was lunching in the staff canteen, but invited me to join her and her colleague, Mr Mushitu Mukwame, who, as luck would have it, is the Head of NBC Radio Services. As she pushed away her plate she exclaimed: “We have been waiting for you!” It seems the NBC has received a government directive to produce 80% local content on radio. !Ah radio, the Ju|’hoan station, is falling short of this target (due largely to the logistical problems of getting out into the bush to gather news and stories, the !Ah producers told me.) But a radio drama, created by local people for local people, would help. If a 13-episode pilot proved successful, said Ms Muinjo, the show could run and run. Thirteen episodes… I began to sweat. Ms Muinjo liked the idea so much she phoned the Director General’s secretary and asked for a meeting then and there. Granted. So up the executive staircase we climbed, and I soon found myself pitching the idea to the Director-General himself, Mr Stanley Similo. He nodded throughout and confirmed the NBC would like to partner with us (Gulp. I’d only just had the idea. My employer, the University of Wolverhampton, knew nothing about it yet. Any minute now my deodorant would fail.) Mr Similo seemed keen to make a narrative about the training and production of the proposed radio drama for television. To show to a national audience. Also, if successful, the drama could be a model for other radio stations in the country, he said. Gulp-gulp. On the long flight home I wrote copious notes about how this project might actually work. Weirdly, it didn’t scare me. Having worked with the San I know how talented they are. I can almost hear the soundscape of the fictional world they could create, the uniquely Ju|’hoan jingle someone will compose, the appealing characters they will suggest to people the drama. We might have to produce radio scripts in an unconventional way at first, but I’m confident the Ju|’hoansi involved will come up with great story lines and deliver convincing performances. And, I suspect, they’ll improve their reading-writing literacy in their mother-tongue along the way. So all I have to do now is find a sponsor for the training workshops. Anyone know an executive in a soap powder company? Or a media mogul with an active social conscience? * http://www.macalester.edu/educationreform/publicintellectualessay/Gratz. Accessed 1-10-2016 Few parents engage in Adult Literacy programmes on offer; one reason mooted by researchers is lack of access to the labour market, even for reading-writing literates. (Survey by Lee quoted in Hays, 2016:228) Hays, J. Owners of Learning: The Nyae Nyae Village Schools over Twenty Five Years . Switzerland: 2016. Basler Afrika Bibliographien Photo of NBC mast courtesy of #Oma Leon Tsamkxao  Imagine you are the Ju|’hoan parent of a school-age child. If you are lucky enough to live in one of the six settlements that has a Village School, your child will have been receiving a basic education in literacy and numeracy in your mother-tongue, until Grade 4 (aged 11, ideally.) While the (usually) lone teacher works largely to the national Namibian curriculum, the teaching is culturally appropriate, so your child is never singled out for punishment or praise (there are no tall poppies in a San field) and work is done collaboratively wherever possible. (The San are renowned peer-educators.) The teacher understands that part of your child’s education must, of necessity, involve learning bush survival skills, so when you all take off in Mangetti season to harvest this sustaining fruit from a faraway dune area, or on rare occasions, to skin and butcher a donated carcass at a distant trophy hunting camp, there is no retribution. More often than you would like, the teacher is absent from school – he has to collect his salary from the nearest big town, Grootfontein, more than 400 km away; he has no transport so must sit beside the ‘Great White Way’ until he can get a lift. This can take days, but apparently, there’s no other payment method. Consequently your child misses out on many teaching days so her progress is slower than expected by the education authorities. But eventually, she is ready for high school. The only high school is in Tsumkwe, so your child will have to board in the hostel. You will miss curling your body around hers in the family hut on cold nights, but she will have a nice new blanket from the government to keep her warm. And a regular supply of maize meal, thanks to the government’s Food Allocation Programme*. That’s more than you can provide for her at home with bush food so scarce. Little Be worries that she won’t understand anything because the teaching medium is English, but you stress that it will get easier if she just sits quietly and does what she sees the other children doing. You are surprised when after just two weeks your studious child turns up outside your hut one evening. She explains that she does not wish to return to the high school; her reason – she does not like being beaten. You are shocked; why would anyone beat a child? Turns out she was found sleeping in the bed of Di||xao, her cousin. N!unkxa, another girl from the village, was sleeping under the same blanket too. You wonder why this is punishable; Di||xao and Be have slept together, in the family hut, under the same blanket, since Di||xao’s mother died in 2011. And N!unkxa is like family. “What happened to your government blanket?” you ask her. “The big boys took it when they mocked me.” The big boys are the Herero, Ovambo or perhaps Kavango children at the high school. They are bigger people and you have heard some make sport from insulting the San. “Did you tell your teacher?” “Yes, but he is the one who beat me.” The above scenario is based on current facts. In 2016 there was only one student registered as San in the higher grades (Grade 10) at Tsumkwe Secondary school. Five years ago UNICEF reported that “the ‘survival rate’ for San students past Grade 7 remains very low compared to the national average… Despite Namibia’s progressive policies, and concern for educationally marginalized children, existing statistics all point to a very low participation by San children in the mainstream education system, especially from the upper primary school onwards.” (Hays, 2016. pp 118-11 **) It is widely documented that poverty, stigmatization, bullying, corporal punishment and even instances of sexual abuse are the reasons for low attendance. Anthropologist, Jennifer Hays (2016: 224) suggests that one must also consider that the lack of participation (in formal education) is in fact a form of resistance. Parents and children are unlikely to subscribe to a system that does not respect their culture. And then there is the problem of employment. There are no jobs to be had in Tsumkwe, educational level notwithstanding. So it would not be surprising if parents prioritized bush learning (tracking, trapping, foraging, traditional crafts which can be sold) over school learning (literacy and numeracy). Yet, they don’t. Every Ju|’hoan adult I spoke to either expressed regret at their own lack of formal education, or at the fact that their children could not be persuaded to continue with secondary education. (Children's rights are respected in this culture. Children are never coerced into doing anything.) Again and again I heard people express the wish for the Village School Project (more about that in the next posting) with its culturally-mediated system to be extended beyond Grade 4; or for there to be a San-only high school in Tsumkwe. But the Namibian government is committed to uniting the disparate ethnic groups in the country so the chances for that seem slim. * The Namibian government allocates some food and a blanket for all children in need. Most Ju|’hoan children are registered “In Need”. Despite this policy, the food sometimes doesn’t make it as far as Tsumkwe. ** Hays, J. Owners of Learning: The Nyae Nyae Village Schools over Twenty Five Years . Switzerland: 2016. Basler Afrika Bibliographien  I’ve shown Tsamkxao, one of the guides at the lodge, my photos of the Ju|’hoan people I met in this area when I first visited in 1994. “Do you know her?” I ask, pointing to a picture of a solemn young woman I’ve always thought of as Koba, namesake of the heroine in my novels, Salt and Honey and Kalahari Passage. “Yes. She’s Koba.” Bingo! I feel breathless, almost afraid to ask the next question. “Where does she live?” “In Makuri.” I knew it was too good to be true. Makuri is an outlying settlement, deep in a baobab forest. It’s 4-wheel drive territory. My little Polo won’t make it. “But she is here now, for the Devil’s Claw harvest,” Tsamkxao adds, unaware of how his casual words make my heart soar. “C-could you s-show me where she is staying?” “Yes… tomorrow.” Overnight I think long and hard about the debt an author owes to person whose name they used for a fictional character. Beside her name, I knew nothing personal about the young woman in the woollen yellow hat I spent a few hours with all those years ago. I was the group’s first eco-tourist back in the day when they were trying to work out how to monetize the only thing they had, namely, their culture. They took me foraging, showed me how to make fire by rubbing sticks, danced and sang a traditional song. I had no language in common with Koba, and even if I’d had, she was so shy I doubt she’d have said a word. I requisitioned her name for my protagonist simply because it was, to my mind, one of the more easily pronounceable San names I heard at the time, being free of the clicks and click-consonants that Westerners find so difficult. I knew nothing about the real Koba’s life but I hoped it was nothing like the tragic one I invented for my heroine. I tossed and turned trying to work out how to explain to a non reading- and writing-literate person what a novel is. (I didn’t know for sure, but chances were that Koba had never turned the pages of any book, having had no formal schooling. It’s estimated that even today 50% of San have never been to school and 90% of those who have, drop out long before they receive a certificate. There are understandable reasons for this. More about those in another blog post.) Given my ignorance about her, I was afraid that a gift of one of my novels, containing a heartfelt dedication, would be tactless. Anyway, how would I explain that my naïve intention to do some consciousness-raising on behalf of the beleaguered San via my novels, had not been commercially successful? The next morning I pack sugar, maize meal, tea and milk powder into the boot of my car, along with a symbolic gift, a striking bead necklace. 22 years ago Koba sold me a necklace she’d made. It seems fitting to bring her one now. Tsamkxao directs me to the outskirts of the town and I pull up outside a neat plot containing temporary-looking shelters made from plastic sheeting and zinc. There is also a two-man tent and in front of this a woman squats; she’s washing something in a plastic bucket. Tsamkxao whispers that this is Koba but I’m doubtful. This woman looks older than I am, when in fact, Koba, by my reckoning, must be 20 years younger. But he insists it’s the Koba from Makuri. I’m shocked, seeing as never before the toll material impoverishment takes on a woman’s life. Now we are face-to-face. Koba looks wary and I recognize that look, those deep-set eyes from my decades-old picture of her. Tsamkxao explains that we have met before but I see no recognition on Koba’s face as she continues to rub soap on the clothing in the bucket. I remind myself that to the San we whites all look the same. Also Koba hasn’t had a constant photographic reminder on her desk, as I have. I hand the photographs of my original encounter with Koba’s people at Makuri, to her. I remind her that I was their first eco-tourist. Tsamkxao translates but she says nothing, just stares intently. I wonder if she has eye problems. The whites of her eyes aren’t white at all, but dull and she has dark circles under each eye. I daren’t ask. I turn my attention to the open-faced child seated next to her. “Your daughter?” I ask. But it turns out that Koba has no children. My novelist’s imagination goes into overdrive – is that why she looks so sad? I leave the photos and food parcel with Koba along with the gleaming necklace – glamour incongruous with the over-washed t-shirt and headscarf Koba is wearing, but she almost smiles as the girl, her niece, exclaims in admiration. Almost, but not quite. I castigate myself for not bringing along a mirror so she could see herself. “I’ll be back,” I promise Koba. “Is there anything I should bring you?” She demurs, then after some prompting, speaks very softly to Tsamkxao. “She asks for shoes,” he translates. I stare down at her very small bare feet; my shoes would swamp her. As I trudge back to my car through the thick sand I wonder where one can buy shoes in this town. I’m beginning to get the idea of what my duty is to my muse.  Sitting on a thatched terrace to write this, looking out at thornscrub lacy grey with Kalahari dust. Lots of red-eyed bulbuls hopping around in the baby baobabs planted around round and I hear the ubiquitous loeries crying 'Go’way' as someone nears their roost. Bushwalk this morning to take the sandwiches we make at breakfast to some hungry kids. In fact, everyone is hungry here: no money to buy food plus the drought and illegal herds of cattle and goats from the invading Herero pastoralists having denuded all bush food. However, one seldom encounters begging. Hawkers try to sell one beadwork or animal carvings, but they accept a refusal immediately. Food given to a San person is immediately shared. I see the sandwich, originally cut into four, divided and divided again until the 16 people who have materialized around the recipient, all have barely a mouthful. Tomorrow I must make two sandwiches, I tell myself, plus sneak some bacon and a boiled egg from the table. During the walk I spy big, crinkly footprints made by elephant who visited the water hole last night. Towards midnight I watched three young bulls materialize, drink their gargantuan fill, then melt away like hulking, grey ghosts – massive one minute, invisible the next. How do they do it? The lodge where I’m staying pumps precious borehole water into a pan to prevent the elephant from breaking into the camp to get at the water tanks. In the evening we call on Melissa’s ‘relatives’, a Ju|’hoan family whose aunt became Melissa’s ‘big name’, thereby adopting her, 25 years ago. The patriach is known as ‘Chief’ Bobo because he is the Tsumkwe delegate on the Traditional Council, a Namibian politico-civic organisation that ensures ethnic representation in national government. Chief Bobo’s family are town dwellers and have a small brick house, far too small to accommodate the extended family group they live in, judging by the number of sleeping mattresses outside. The one tree on the fenced-off property serves as storage space and is hung with blankets and clothing. It seems cooking is still done outside, as we see a woman squatting next to a frugal fire making maize meal porridge in a small, blackened pot. Some painfully thin dogs and a few tiny puppies snuffle around. They say the canine population is always an indication of food availability. Counting the protruding ribs on these mutts, I’d say things are bleak. The elderly matriarch, //Ui ce, seems serene. She and her handsome older sister are engaged in making beads from a bag of ostrich eggshell shards. They are using nail clippers to shape the beads rather than nibbling them into rounds, as in the past. Much better for their teeth, I’m sure. As the sun sets, adolescents flock home, chirping and giggling. Several of the girls are wearing candy-striped knee-high socks (the General dealer has just had a shipment in) it being a wintery 20 degrees. With their graceful necks and long pink legs, the San girls remind me of flamingoes. There is consternation here as an army base is to be built nearby and people fear for the safety of their girls. In this and other San areas, sexual harassment from other ethnic groups is a real and present danger. However, the base will mean employment for some Ju|’hoan people; having been forced into the cash economy, all need income. Another of the intractable problems the modern world has forced upon this ancient hunter-gatherer culture.

|

AuthorAfrican novelist and out-to-grass, academic. Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed