Imagine you are the Ju|’hoan parent of a school-age child. If you are lucky enough to live in one of the six settlements that has a Village School, your child will have been receiving a basic education in literacy and numeracy in your mother-tongue, until Grade 4 (aged 11, ideally.) While the (usually) lone teacher works largely to the national Namibian curriculum, the teaching is culturally appropriate, so your child is never singled out for punishment or praise (there are no tall poppies in a San field) and work is done collaboratively wherever possible. (The San are renowned peer-educators.) The teacher understands that part of your child’s education must, of necessity, involve learning bush survival skills, so when you all take off in Mangetti season to harvest this sustaining fruit from a faraway dune area, or on rare occasions, to skin and butcher a donated carcass at a distant trophy hunting camp, there is no retribution. More often than you would like, the teacher is absent from school – he has to collect his salary from the nearest big town, Grootfontein, more than 400 km away; he has no transport so must sit beside the ‘Great White Way’ until he can get a lift. This can take days, but apparently, there’s no other payment method. Consequently your child misses out on many teaching days so her progress is slower than expected by the education authorities. But eventually, she is ready for high school. The only high school is in Tsumkwe, so your child will have to board in the hostel. You will miss curling your body around hers in the family hut on cold nights, but she will have a nice new blanket from the government to keep her warm. And a regular supply of maize meal, thanks to the government’s Food Allocation Programme*. That’s more than you can provide for her at home with bush food so scarce. Little Be worries that she won’t understand anything because the teaching medium is English, but you stress that it will get easier if she just sits quietly and does what she sees the other children doing. You are surprised when after just two weeks your studious child turns up outside your hut one evening. She explains that she does not wish to return to the high school; her reason – she does not like being beaten. You are shocked; why would anyone beat a child? Turns out she was found sleeping in the bed of Di||xao, her cousin. N!unkxa, another girl from the village, was sleeping under the same blanket too. You wonder why this is punishable; Di||xao and Be have slept together, in the family hut, under the same blanket, since Di||xao’s mother died in 2011. And N!unkxa is like family. “What happened to your government blanket?” you ask her. “The big boys took it when they mocked me.” The big boys are the Herero, Ovambo or perhaps Kavango children at the high school. They are bigger people and you have heard some make sport from insulting the San. “Did you tell your teacher?” “Yes, but he is the one who beat me.” The above scenario is based on current facts. In 2016 there was only one student registered as San in the higher grades (Grade 10) at Tsumkwe Secondary school. Five years ago UNICEF reported that “the ‘survival rate’ for San students past Grade 7 remains very low compared to the national average… Despite Namibia’s progressive policies, and concern for educationally marginalized children, existing statistics all point to a very low participation by San children in the mainstream education system, especially from the upper primary school onwards.” (Hays, 2016. pp 118-11 **) It is widely documented that poverty, stigmatization, bullying, corporal punishment and even instances of sexual abuse are the reasons for low attendance. Anthropologist, Jennifer Hays (2016: 224) suggests that one must also consider that the lack of participation (in formal education) is in fact a form of resistance. Parents and children are unlikely to subscribe to a system that does not respect their culture. And then there is the problem of employment. There are no jobs to be had in Tsumkwe, educational level notwithstanding. So it would not be surprising if parents prioritized bush learning (tracking, trapping, foraging, traditional crafts which can be sold) over school learning (literacy and numeracy). Yet, they don’t. Every Ju|’hoan adult I spoke to either expressed regret at their own lack of formal education, or at the fact that their children could not be persuaded to continue with secondary education. (Children's rights are respected in this culture. Children are never coerced into doing anything.) Again and again I heard people express the wish for the Village School Project (more about that in the next posting) with its culturally-mediated system to be extended beyond Grade 4; or for there to be a San-only high school in Tsumkwe. But the Namibian government is committed to uniting the disparate ethnic groups in the country so the chances for that seem slim. * The Namibian government allocates some food and a blanket for all children in need. Most Ju|’hoan children are registered “In Need”. Despite this policy, the food sometimes doesn’t make it as far as Tsumkwe. ** Hays, J. Owners of Learning: The Nyae Nyae Village Schools over Twenty Five Years . Switzerland: 2016. Basler Afrika Bibliographien

6 Comments

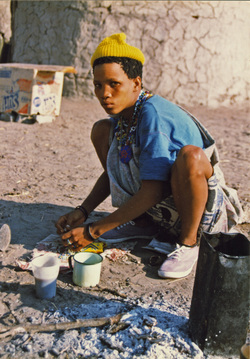

I’ve shown Tsamkxao, one of the guides at the lodge, my photos of the Ju|’hoan people I met in this area when I first visited in 1994. “Do you know her?” I ask, pointing to a picture of a solemn young woman I’ve always thought of as Koba, namesake of the heroine in my novels, Salt and Honey and Kalahari Passage. “Yes. She’s Koba.” Bingo! I feel breathless, almost afraid to ask the next question. “Where does she live?” “In Makuri.” I knew it was too good to be true. Makuri is an outlying settlement, deep in a baobab forest. It’s 4-wheel drive territory. My little Polo won’t make it. “But she is here now, for the Devil’s Claw harvest,” Tsamkxao adds, unaware of how his casual words make my heart soar. “C-could you s-show me where she is staying?” “Yes… tomorrow.” Overnight I think long and hard about the debt an author owes to person whose name they used for a fictional character. Beside her name, I knew nothing personal about the young woman in the woollen yellow hat I spent a few hours with all those years ago. I was the group’s first eco-tourist back in the day when they were trying to work out how to monetize the only thing they had, namely, their culture. They took me foraging, showed me how to make fire by rubbing sticks, danced and sang a traditional song. I had no language in common with Koba, and even if I’d had, she was so shy I doubt she’d have said a word. I requisitioned her name for my protagonist simply because it was, to my mind, one of the more easily pronounceable San names I heard at the time, being free of the clicks and click-consonants that Westerners find so difficult. I knew nothing about the real Koba’s life but I hoped it was nothing like the tragic one I invented for my heroine. I tossed and turned trying to work out how to explain to a non reading- and writing-literate person what a novel is. (I didn’t know for sure, but chances were that Koba had never turned the pages of any book, having had no formal schooling. It’s estimated that even today 50% of San have never been to school and 90% of those who have, drop out long before they receive a certificate. There are understandable reasons for this. More about those in another blog post.) Given my ignorance about her, I was afraid that a gift of one of my novels, containing a heartfelt dedication, would be tactless. Anyway, how would I explain that my naïve intention to do some consciousness-raising on behalf of the beleaguered San via my novels, had not been commercially successful? The next morning I pack sugar, maize meal, tea and milk powder into the boot of my car, along with a symbolic gift, a striking bead necklace. 22 years ago Koba sold me a necklace she’d made. It seems fitting to bring her one now. Tsamkxao directs me to the outskirts of the town and I pull up outside a neat plot containing temporary-looking shelters made from plastic sheeting and zinc. There is also a two-man tent and in front of this a woman squats; she’s washing something in a plastic bucket. Tsamkxao whispers that this is Koba but I’m doubtful. This woman looks older than I am, when in fact, Koba, by my reckoning, must be 20 years younger. But he insists it’s the Koba from Makuri. I’m shocked, seeing as never before the toll material impoverishment takes on a woman’s life. Now we are face-to-face. Koba looks wary and I recognize that look, those deep-set eyes from my decades-old picture of her. Tsamkxao explains that we have met before but I see no recognition on Koba’s face as she continues to rub soap on the clothing in the bucket. I remind myself that to the San we whites all look the same. Also Koba hasn’t had a constant photographic reminder on her desk, as I have. I hand the photographs of my original encounter with Koba’s people at Makuri, to her. I remind her that I was their first eco-tourist. Tsamkxao translates but she says nothing, just stares intently. I wonder if she has eye problems. The whites of her eyes aren’t white at all, but dull and she has dark circles under each eye. I daren’t ask. I turn my attention to the open-faced child seated next to her. “Your daughter?” I ask. But it turns out that Koba has no children. My novelist’s imagination goes into overdrive – is that why she looks so sad? I leave the photos and food parcel with Koba along with the gleaming necklace – glamour incongruous with the over-washed t-shirt and headscarf Koba is wearing, but she almost smiles as the girl, her niece, exclaims in admiration. Almost, but not quite. I castigate myself for not bringing along a mirror so she could see herself. “I’ll be back,” I promise Koba. “Is there anything I should bring you?” She demurs, then after some prompting, speaks very softly to Tsamkxao. “She asks for shoes,” he translates. I stare down at her very small bare feet; my shoes would swamp her. As I trudge back to my car through the thick sand I wonder where one can buy shoes in this town. I’m beginning to get the idea of what my duty is to my muse.  Sitting on a thatched terrace to write this, looking out at thornscrub lacy grey with Kalahari dust. Lots of red-eyed bulbuls hopping around in the baby baobabs planted around round and I hear the ubiquitous loeries crying 'Go’way' as someone nears their roost. Bushwalk this morning to take the sandwiches we make at breakfast to some hungry kids. In fact, everyone is hungry here: no money to buy food plus the drought and illegal herds of cattle and goats from the invading Herero pastoralists having denuded all bush food. However, one seldom encounters begging. Hawkers try to sell one beadwork or animal carvings, but they accept a refusal immediately. Food given to a San person is immediately shared. I see the sandwich, originally cut into four, divided and divided again until the 16 people who have materialized around the recipient, all have barely a mouthful. Tomorrow I must make two sandwiches, I tell myself, plus sneak some bacon and a boiled egg from the table. During the walk I spy big, crinkly footprints made by elephant who visited the water hole last night. Towards midnight I watched three young bulls materialize, drink their gargantuan fill, then melt away like hulking, grey ghosts – massive one minute, invisible the next. How do they do it? The lodge where I’m staying pumps precious borehole water into a pan to prevent the elephant from breaking into the camp to get at the water tanks. In the evening we call on Melissa’s ‘relatives’, a Ju|’hoan family whose aunt became Melissa’s ‘big name’, thereby adopting her, 25 years ago. The patriach is known as ‘Chief’ Bobo because he is the Tsumkwe delegate on the Traditional Council, a Namibian politico-civic organisation that ensures ethnic representation in national government. Chief Bobo’s family are town dwellers and have a small brick house, far too small to accommodate the extended family group they live in, judging by the number of sleeping mattresses outside. The one tree on the fenced-off property serves as storage space and is hung with blankets and clothing. It seems cooking is still done outside, as we see a woman squatting next to a frugal fire making maize meal porridge in a small, blackened pot. Some painfully thin dogs and a few tiny puppies snuffle around. They say the canine population is always an indication of food availability. Counting the protruding ribs on these mutts, I’d say things are bleak. The elderly matriarch, //Ui ce, seems serene. She and her handsome older sister are engaged in making beads from a bag of ostrich eggshell shards. They are using nail clippers to shape the beads rather than nibbling them into rounds, as in the past. Much better for their teeth, I’m sure. As the sun sets, adolescents flock home, chirping and giggling. Several of the girls are wearing candy-striped knee-high socks (the General dealer has just had a shipment in) it being a wintery 20 degrees. With their graceful necks and long pink legs, the San girls remind me of flamingoes. There is consternation here as an army base is to be built nearby and people fear for the safety of their girls. In this and other San areas, sexual harassment from other ethnic groups is a real and present danger. However, the base will mean employment for some Ju|’hoan people; having been forced into the cash economy, all need income. Another of the intractable problems the modern world has forced upon this ancient hunter-gatherer culture.

Courtesy of my employer, the University of Wolverhampton, I received funding to undertake a reccie to Nyae Nyae, homeland of the Ju|’hoansi San in North-eastern Namibia. My aim was to investigate reading/writing literacy among this group of former hunter-gatherers. Personally, I was hoping to find a San writer I could mentor so s/he could write first-hand about the experiences of this, one of the world’s oldest and most marginalized indigenous people.

I was able to coincide my visit with that of Melissa Heckler, founding teacher of the Village Schools Project, which offers culturally-mediated mother–tongue education to Ju|’hoan children in remote areas, so I was keen to learn about this renowned literacy initiative. But first we had to get there. One reaches Nyae Nyae by crossing the African continent, then travelling 670 km north from Windhoek, the capital city of Namibia. We passed troupes of baboon which live in the copper-coloured hills surrounding the city, then entered a seemingly endless savannahscape: dark umbrella-shaped thorn trees protruding above an ocean of bleached grass; families of warthog on calloused knees rooting around on the verges; roan antelope and once, a rare Nyala gazing out from behind a high game fence. The road goes on and on and on and on, but I was with one of the world’s top storytellers so the kilometers flew by. I'd barely registered the turn off to the big meteor crash site near Grootfontein before we were on the 'Great White Way', the gravel road that leads ultimately to the border between Namibia and Botswana. It’s a hot and dusty 5-hour drive through thorn scrub that's tinder-dry after a long drought. Veld fires, set and accidental, are common, and I was relieved that the wide road acted as firebreak to the inferno we encountered on our right-hand side. The not-so-hard shoulder of this road (beware deep, sucking sand turned glassy by the intense heat) was a feeding station for the startlingly coloured lilac-breasted rollers who waited there to gobble up grasshoppers fleeing the flames. I've never seen so many rollers concentrated in one space. They say every bird has 27 colours in its plumage and I can vouch for the fact that the turquoise-blue wings alone are dazzling against the backdrop of charred veld. Finally a transmission tower appeared on the horizon (Remember this tower; it looms large in my new project) and Melissa craned forward. This was her seventeenth trip to the Nyae Nyae Conservancy since she started the first Village school 25 years ago. Some of the Ju|’hoan children she taught are now adults and send their children to Village schools. On this visit Melissa planned to initiate a pre-school program for the new generation of Ju|’hoan children. I had personal reasons for feeling excited. It was 22 years since I‘d visited this area and I hoped to meet up with some of the people who unwittingly inspired my first novel, Salt & Honey. I figured the chances were slim; they were nomadic, the group may have disbanded, people could have died. And I wasn't sure how close to Tsumkwe, the town where I'd be based, they had been. Still, strange things happen in the Kalahari; as Melissa says, you've just got to be there. |

AuthorAfrican novelist and out-to-grass, academic. Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed