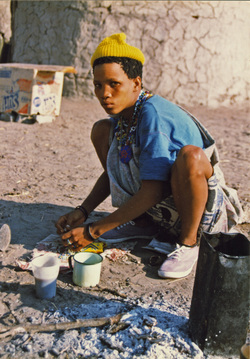

I’ve shown Tsamkxao, one of the guides at the lodge, my photos of the Ju|’hoan people I met in this area when I first visited in 1994. “Do you know her?” I ask, pointing to a picture of a solemn young woman I’ve always thought of as Koba, namesake of the heroine in my novels, Salt and Honey and Kalahari Passage. “Yes. She’s Koba.” Bingo! I feel breathless, almost afraid to ask the next question. “Where does she live?” “In Makuri.” I knew it was too good to be true. Makuri is an outlying settlement, deep in a baobab forest. It’s 4-wheel drive territory. My little Polo won’t make it. “But she is here now, for the Devil’s Claw harvest,” Tsamkxao adds, unaware of how his casual words make my heart soar. “C-could you s-show me where she is staying?” “Yes… tomorrow.” Overnight I think long and hard about the debt an author owes to person whose name they used for a fictional character. Beside her name, I knew nothing personal about the young woman in the woollen yellow hat I spent a few hours with all those years ago. I was the group’s first eco-tourist back in the day when they were trying to work out how to monetize the only thing they had, namely, their culture. They took me foraging, showed me how to make fire by rubbing sticks, danced and sang a traditional song. I had no language in common with Koba, and even if I’d had, she was so shy I doubt she’d have said a word. I requisitioned her name for my protagonist simply because it was, to my mind, one of the more easily pronounceable San names I heard at the time, being free of the clicks and click-consonants that Westerners find so difficult. I knew nothing about the real Koba’s life but I hoped it was nothing like the tragic one I invented for my heroine. I tossed and turned trying to work out how to explain to a non reading- and writing-literate person what a novel is. (I didn’t know for sure, but chances were that Koba had never turned the pages of any book, having had no formal schooling. It’s estimated that even today 50% of San have never been to school and 90% of those who have, drop out long before they receive a certificate. There are understandable reasons for this. More about those in another blog post.) Given my ignorance about her, I was afraid that a gift of one of my novels, containing a heartfelt dedication, would be tactless. Anyway, how would I explain that my naïve intention to do some consciousness-raising on behalf of the beleaguered San via my novels, had not been commercially successful? The next morning I pack sugar, maize meal, tea and milk powder into the boot of my car, along with a symbolic gift, a striking bead necklace. 22 years ago Koba sold me a necklace she’d made. It seems fitting to bring her one now. Tsamkxao directs me to the outskirts of the town and I pull up outside a neat plot containing temporary-looking shelters made from plastic sheeting and zinc. There is also a two-man tent and in front of this a woman squats; she’s washing something in a plastic bucket. Tsamkxao whispers that this is Koba but I’m doubtful. This woman looks older than I am, when in fact, Koba, by my reckoning, must be 20 years younger. But he insists it’s the Koba from Makuri. I’m shocked, seeing as never before the toll material impoverishment takes on a woman’s life. Now we are face-to-face. Koba looks wary and I recognize that look, those deep-set eyes from my decades-old picture of her. Tsamkxao explains that we have met before but I see no recognition on Koba’s face as she continues to rub soap on the clothing in the bucket. I remind myself that to the San we whites all look the same. Also Koba hasn’t had a constant photographic reminder on her desk, as I have. I hand the photographs of my original encounter with Koba’s people at Makuri, to her. I remind her that I was their first eco-tourist. Tsamkxao translates but she says nothing, just stares intently. I wonder if she has eye problems. The whites of her eyes aren’t white at all, but dull and she has dark circles under each eye. I daren’t ask. I turn my attention to the open-faced child seated next to her. “Your daughter?” I ask. But it turns out that Koba has no children. My novelist’s imagination goes into overdrive – is that why she looks so sad? I leave the photos and food parcel with Koba along with the gleaming necklace – glamour incongruous with the over-washed t-shirt and headscarf Koba is wearing, but she almost smiles as the girl, her niece, exclaims in admiration. Almost, but not quite. I castigate myself for not bringing along a mirror so she could see herself. “I’ll be back,” I promise Koba. “Is there anything I should bring you?” She demurs, then after some prompting, speaks very softly to Tsamkxao. “She asks for shoes,” he translates. I stare down at her very small bare feet; my shoes would swamp her. As I trudge back to my car through the thick sand I wonder where one can buy shoes in this town. I’m beginning to get the idea of what my duty is to my muse.

3 Comments

Micky Kruger

9/8/2016 11:48:43 pm

Oh this is so fascinating Candy, going back after all this time, and finding Koba. You really do lead such an interesting life my friend! So proud of you and all you have achieved..and waiting to read of your next encounter!

Reply

Rutger Schuitemaker

7/4/2019 03:41:11 pm

Moving, very moving. High impact. About human connection of a different kind. Story important to share with the world. Cultural anthropology too, real fieldwork.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorAfrican novelist and out-to-grass, academic. Archives

January 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed