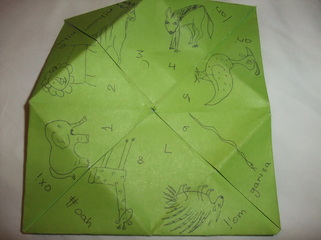

!’o !oahn !’o ||hai Do you remember, as a child, making Fortune Tellers out of intricately folded paper? Dunno about you but we pre-teens used them to tease one another about our destinies: mode of transport, type of job, and yeah, love interest. I’ve heard Origamists call them flowers but to my mind they better resemble a beak because of the way they open and close when one manipulates them. It occurred to me that it might make a useful story prompt for Village School pupils if the choices were divided into culturally appropriate Character, Setting and Feeling options. It would enable the class to work in groups, clustered around one origami flower – or Story Starter, as I came to call them. Children could create a tale collaboratively, which is the preferred way of working for most San learners. (Co-operation and sharing being survival essentials for hunter-gatherers in a challenging environment.) I wrote numbers on the outer ‘petals’ of the flower and the Ju|’hoan names of various animals well-known to them on the next layer of quadrants: (porcupine, snake, lion, elephant, etc.) My first model failed due to the children’s lack of literacy. However, they were all intrigued by the mechanics of the paper device and were eager to make their own. For Story Starter Mach 2, I drew the animals (characters) onto every quadrant, using cartoon style in some instances and a realistic ink drawing in others. (See images below.) I wanted to test whether the illustration style had any effect on visual comprehension. It didn’t. The cartoon lion was perceived as easily as the realistic kudu buck, the cartoon building with a red cross as easily as the more accurately drawn acacia tree. I found I had to spend too much of the lesson helping pupils with the complicated folding as they tried to make their own Story Starters. Also, to my surprise, all the pupils, even the older ones, struggled with the opening and closing motion (the bird’s beak movement, in other words) in horizontal and vertical planes. This, as you’ll know, is essential for the manipulation of the fortune-teller. I consulted with Bruce Parcher and Melissa Heckler, both early education specialists who have more than 30 years experience of teaching the San, between them. They felt a degree of fine motor co-ordination was necessary. Could it be that without exposure to the educational toys taken for granted in pre-schools, the San only develop these skills later, they wondered? A research topic perhaps, but in the meantime Melissa suggested a prep. exercise to help the children master the left-right opening action:pulling and pushing the ends of a piece of string. Fortunately I'd brought a bag of invitingly coloured and textured string along. The third time I ran this creative writing exercise I handed out a length of string to every child. Together we chanted the Ju|’hoan words for close (!’o) and open (!oahn) while we practiced thumb and forefinger co-ordination. Then I handed out a supply of origami flowers made in advance by Melissa Heckler – on her lap, in the passenger seat, as I drove to the Village School. The woman is a paper-folding machine! She produced 20 perfect devices while being shaken like a cocktail over the dirt road corrugations. Now every child had a chance to try operating the Story Starter and thanks to a chant of "Close-open-close-pull" — !’o !oahn !’o ||hai – it worked well.

0 Comments

The bush telegraph in Tsumkwe is as fast as the internet is slow. Within one day of starting my pop-up creative writing workshop in the children’s section of the Tsumkwe public library, the number of participants doubled, then doubled again. The small space, supervised by the charming, young Administrative Assistant called N#aisa Ghauz, soon filled to capacity with primary- and secondary-school-aged children from the town’s multi-ethnic population. True, I’d brought along a giant box of crayons and some sweet fruit treats, but it was the origami device I made that kept them intrigued. This was an early prototype of the Story Starter and featured numerals and words, the words written in Ju|’hoan. (Problematic, as it turned out the majority of children weren’t Ju|’hoan. I saw for myself what educationalist had reported, viz. that Ju|’hoan children are reluctant to mix with their multi-ethnic peers; the few that approached the teaching table were soon elbowed out by physically bigger and more confident kids. I have sympathy for the repeated requests by the Ju|’hoan community for a mother-tongue school in the town. However, it’s contrary to Namibia’s laudable inclusion policy. Clearly, attitudes on both sides need to change – the San need to build confidence, their neighbours need to gain respect for them. Hearteningly, the Director-General of the Namibian Broadcasting Corporation mentioned something to me that just might help in this regard. More about that when I blog about my new project idea.) In the meantime, I was here to investigate local literacy levels, so I switched to oral teaching using English, Afrikaans and illustrations to explain building a story together from chosen elements on the device. Lots of paper-folding, drawing and laughing later, one group of youngsters did produce a tale, much to N#aisa’s surprise. “The children come to the library after school,” she explained, “but most just look at the pictures in the books. They don’t like to read or write.” Yes, few wrote, but all wanted to draw and proved excellent copyists when I demo-ed cartooning (to the best of my limited ability) the various animals they chose as story protagonists. One group of youngsters dictated a short but complete story, which they called Oscar and the Snake*. See it here. It’s been translated into Ju|’hoan by a local interpreter, !Ui Charlie Ngeisi. Once he uploads this will be the first, original, stakeholder-created Ju|’hoan story on the site. But upload could take a while. Participating in the digital world is a challenge when one lives as remotely as !Ui Charlie and the people of Nyae Nyae do.

( ‘Trrrrr-trrrrr-trrrr’ is the sound an agitated porcupine makes by bristling its quills. My informants were the children of Duin Pos village school who live alongside porcupines, pangolins and much larger wildlife in the Nyae Nyae Conservancy in Namibia. As you’ll know from my latest Research blogs, one of my objectives of my recent trip was to do some creative writing with school children. The principal of the Village Schools is the wonderfully named Cwisa Cwi, or |Ui’sa |Ui – linguists keep fiddling with the spelling of Ju|’hoan, which, ancient as it probably is, has only had a written form for about 50 years. [This orthographic evolution is going to cause me a headache when it comes to writing the next novel in my Koba series – I have a character named Twi, which is how Cwi used to be spelled. Sorry, writer’s digression, but I feel I’m among friends.] Cwisa invited me to give a few classes in the more accessible Village Schools. These are tented schools in remote, but nevertheless 2WD-reachable settlements, where children aged 6 –10 are given a basic primary education in their mother-tongue. Many children board at the schools as they live too far away to do a daily walk. (Plus they could encounter elephant and lion, the aforementioned wildlife.) This means they are dependent upon the government’s school feeding scheme, well-intentioned, but in practice, unreliable. The food (chiefly maize meal) is often not delivered in time for the term start, or an insufficient amount is sent so it runs out before the end of the term. When this happens the children have no choice but to leave for their home villages, often sitting at the side of the road for many hours hoping for a lift. Once home, food is likely to be scarce too, given the long-standing drought in the region and consequently the scarcity of bush foods. It was no surprise at Duin Pos to see the school ‘canteen’, a lone three-legged pot on an unlit fire, deserted. But the tented classroom was full, pupils ranging from 5 to 16. (I’m assuming that the older boys and girls were ‘drop outs’ from Tsumkwe Secondary school who experienced one or more the issues I’ve described in my blog post: The School Problem.) I designed a “Story Starter”, an adapted origami fortune-teller that offers Character, Setting and Feeling choices (culturally relevant ones, e.g. Hyena, Bush camp and Feeling hungry) as a hands-on writing prompt. More about this in the !’o !oahn !’o ||hai post – suffice to say it helped the group to produce a collaborative story, very short, but original – a first for them, their teacher said. I called their story ‘Trrrr Trrrr Trrrr’ as the class came alive when I asked them what sound the main character they’d chosen for the story, viz. a porcupine, makes. (Oral learners, see. ) I’ll upload this story (in English) onto the website called African Storybook. This site is a great resource for teachers, writers and early learners. It features Afro-centric stories in more than 200 African languages. In due course I hope to have ‘Trrr-trrrr-trrr’ translated into Ju|’hoan. Frustratingly, there is little chance of any of the writers seeing their story on the internet: the nearest connection is at the public library in Tsumkwe, where, even if the kids could reach it, the bandwidth is so narrow and in such demand, it’s a major struggle accessing http://www.africanstorybook.org I’m working on a plan to return to Duin Pos to show children their creations on a screen. It’s a small step, but could be important in igniting a spark in a child who is going to become a writer for her/his people. Guilty tastes

I've just read Triomf, Marlene Van Niekerk’s powerful portrayal of post-Apartheid Afrikaners in all their pathos, in English. One day I hope to read it in the original Afrikaans. I grew up in Pretoria, the administrative seat of the Apartheid government, and though my home language was English, I quickly learned to ‘praat die taal’ to avoid being bullied and to help my ‘rooinek’ (Yorkshire-born) mother who never learned to speak Afrikaans and couldn't get served in some shops. My delight in the language itself was my guilty secret all through the Apartheid years. I loved and still do (though my vocabulary is much diminished from lack of use) the full-mouthed taste of Afrikaans words. They satisfy like the English equivalents simply don’t. ‘Full-mouthed’ being a case in point; it’s ‘vol mond’ in Afrikaans and pronouncing it properly involves a veritable feast of maxillo-facial activity: the mouth cavity, the cheeks and both lips. It’s like sucking the sweetness from a whole orange or a granadilla, or mouthing a very ripe guava. Delicious! I think Afrikaans is a robust-sounding, richly onomatopoeic language, not for pronunciation by the mealy-mouthed. I admit that the Afrikaans words that litter my novels are my homage to my clandestine love affair with the language of the Oppressor. I know from conversations I’ve had with readers that words and phrases strike chords with them too. I once had a very jolly experience with a book group in South Africa who were reading Kalahari Passage. They invited me to make a guest appearance via Skype. They told me a Springbok radio jingle I’d referred to in my novel had taken them back to their childhoods. Before long we were I-remember-when-ing and then singing ‘Hospitaal Tyd’ in unison across cyberspace. I have never been able to remember the second verse: Stuur vir my, asseblief, as daar iemand is wat die 'leid en 'n glimlag onthou'.) I was surprised at the Univeristy of Wolverhampton’s International Festival, to hear two students from the Netherlands describe the Afrikaans I was speaking to them for their amusement (I imagine that Afrikaans must sound to contemporary Dutch speakers like 17th century peasant-speak – the Dutch colonized the Cape in the 1650s) as soft. They believe that Dutch is a harsher-sounding language. ‘We call Afrikaans “Baby Dutch,”’ said Ninelin, who reported that she did not have to resort to using the glossary at the back of my novel for the Afrikaans words. The Ju|’hoan ones were more challenging :) So, despite what I believe to be an excellent translation of Triomf by Leon De Kock, I’d still like to have a go at reading it in Afrikaans. If he found that a word like ‘bek’ was best left untranslated – it means mouth, but it’s cruder than that. ‘Gob’ maybe… perhaps that’s too regional – I shall find it fascinating to wrap my mouth around the lexicon of these materially poor but richly imaginative characters.

Start blogging by creating a new post. You can edit or delete me by clicking under the comments. You can also customize your sidebar by dragging in elements from the top bar.

|

AuthorCandi is all sorts: writer, teacher, traveller, dancer, San supporter. And now, a self-publisher. Archives

September 2016

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed